The fascinating life of a Ukrainian refugee in Oregon

“All our family and friends — everybody — went to jail,” says Peter Vins, a former Soviet political prisoner who now works with refugees at Catholic Charities of Oregon.

“They put my grandmother in jail when she was 64 and had cancer. For me growing up, going to jail was like maybe for some Midwestern Americans going into the army. You go to jail, you learn the life, you build character and you become a man.”

Vins, 67, is the son of three generations of Protestant ministers. His grandfather, for whom he was named, was shot during the purges of Joseph Stalin. His father Georgi was sentenced to a total of 13 years in Siberia for preaching the Gospel amid an officially atheist regime.

Vins himself became a religious and human rights activist in 1970s Soviet-era Ukraine, organizing the production and distribution of dissident literature, including Bibles. He had several typists who would crank out copies of books like the Gulag Archipelago by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. The precious and dangerous manuscripts would be loaned to households that had 24 hours to read them and pass them along to stay a step ahead of KGB counterintelligence.

But Vins, being the descendent of prominent dissidents, fell onto the KGB radar. One crew shoved him into a black Volga and drove him into the Woods outside Kiev. An officer warned him to shape up or die before a thug punched him in the face and left him to walk home 30 miles in the snow.

But Vins persisted. Later, a KGB executioner team tried to pull him off the streets of Kiev into a car, but he fought back and alerted neighbors. The KGB, sensing the operation would not be very clean, satisfied itself with snapping one of his legs.

Vins seemed fated for struggle. He was born with dead intestines and was expected to die before reaching age 8. But two U.S. doctors came to Kiev and led a seminar in a life-saving procedure. Then, when he was a boy, he saw his father arrested for talking about love, freedom and faith.

“Life is a wonderful journey, and things happen to you and you look back and sometimes they are completely unbelievable. Youi look back and ask, ‘Did this really happen to me?’”

When Peter himself was finally jailed, he had allies on the inside because of his family history. But the guards were rough on him, hitting him in the stomach while he was just standing around.

Every 12 hours, the new shift of guards would come to his cell and beat him. He had learned from his father and from Solzhenitsyn that going on hunger strike was the only way to avert being battered. So Vins traded punches for pangs and did so gladly.

Missing jail food was not all that distressing. Usually, it was a small bowl of soup with one or two chunks of potato and a few shards of cabbage.

All the while he worked breaking rocks with a sledgehammer or toiled in a factory.

Peter Vins walks down a sidewalk with family 15 minutes after being released from a Soviet work camp in 1979.

After being released and continuing his activism, it seemed Vins would be jailed again – or worse. The hit man who had broken his leg started showing up on the streets, seeking at least to intimidate the young dissident. Vins’ mother, a highly respected high school English teacher, was fired and blacklisted. All this while her husband was in the gulag.

At this bleak time, negotiations started between U.S. President Jimmy Carter and Soviet leaser Leonid Brezhnev. The story of Rev. Georgi Vins had spread and Carter, also a devout Baptist, worked to bring the entire family to the United States by trading two Soviet spies.

“It was like stepping on the moon,” Vins says of the arrival in America. He suffered from nightmares. His overwhelmed aunt cried for two hours after going into a U.S. supermarket. “She couldn’t believe that you can have 20 different types of butter.”

Vins had his own adjusting to do as he was admitted to Dartmouth College, a prestigious Ivy League school. He saw U.S. prep school grads drink beer while writing beautiful papers in less than an hour, while the task took him five or six days.

He landed a job in the college town washing dishes and got a lesson from the owner: Be the best dishwasher we’ve ever seen, and you’ll move up.

Vins graduated from Dartmouth in 1985 and within two years was managing a large hotel. He says the dishwashing gig taught him more than college.

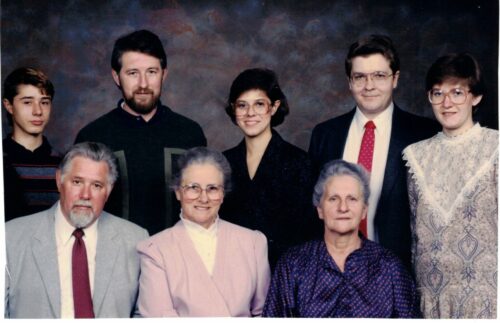

The Vins family after a decade in the United States.

When the Soviet Union fell in the early 1990s, Vins had a flaming urge to return. An enterprising man, he knew an open business opportunity when he saw it. He started a successful logistics and freight firm in Moscow, where sending an armed guard with each truck was common practice.

“If you sent a truck without a Kalashnikov, your cargo 99% would be stolen,” he says with a chuckle.

Serving the U.S. embassy and other big customers, he became locally famous, appearing on the cover of a local trade magazine. But it was a wild time, retaining the instability of the old Soviet Union. He eventually moved to his home town of Kiev, after Russian authorities began to harass him.

“Life [there] never goes smoothly,” Vins explains. “It’s always up and down. One day you are close to death, next day you are close to heaven.”

The close to death part hit hard in February 2022. As Russian troops amassed at the borders of Ukraine, Vins resolved to stay and ride it out. But then he saw his neighbors, many of them in the Ukrainian military, start to evacuate their families. Then shells began to land in Kiev. He and his wife and son packed quickly and drove west just before bombs started to fall.

Peter Vins with his wife and son during their grueling escape from Ukraine during the 2022 Russian invasion.

They tried different border crossings and met long wait times and exhaustion. But eventually they reached Poland, survived a freezing night in a hotel room with no heat, and then came to Portland, where Vins’ brother lives.

“It is important for Ukraine that people in the U.S. and understand that this is not just our war, it’s a war for democracy,” Vins says, reflecting on his escape. “I am a refugee. I have no pension. I have no savings. They are all back home in Ukraine. I am 67 and I have to work to pay my bills.”

He waited tables during his first six months in Portland but then was offered a job at Catholic Charities.

“If I can help somebody, if I can do something positive, I get this as a boomerang that comes back to me,” Vins says.

He was frightened when he started the job, since he’d spent 30 years working for himself. But soon his fears were dispelled.

“The way the team took me in and the way people on the team treated me — I have found a second home,” he says. “It’s a good team, good people and a good cause. When you look at the people, our clients, the refugees, and you see the achievements they have made in six months, you realize we are doing something good.”

SEE VIDEO:

PHOTOS

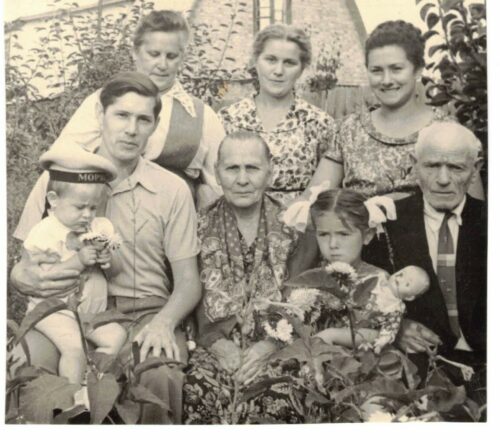

The Vins family visits their jailed husband and father in the mid-1960s.

The grandfather and father of Peter Vins. The grandfather would be shot in a Soviet prison and the father would spend years in a Siberian gulag before being traded to the United States for two Soviet spies.

Young Peter Vins sits on his father’s lap in this family photo from Ukraine in the late 1950s.

Peter Vins, left, enjoys time with a crew that helped a refugee family move into housing. The family’s faces have been intentionally obscured for their protection.

The Catholic Charities ID card of Peter Vins. He was nervous when he started working for the Portland nonprofit but now considers it his second home.